Dictionaries and Semantic Grounding

Here's a thought experiment which we owe to Stephen Harnad. Picture an English speaker who doesn't speak Chinese. Give them a Chinese monolingual dictionary and ask them to learn to speak Chinese from that dictionary alone. Take delight in their puzzled look as they wonder what is wrong with you. If they haven't given up on you at this stage, congratulations I guess: you managed to find a true friend that will stick with you even when you're way too deep into your nerdy science & philosophy papers.

Here's the interesting point behind that quirky setup: you can't learn a language from pure text alone. More precisely, you might be able to identify the structure of each sentence, and you might learn that some characters may be swapped for their definitions. Here are a couple actual Chinese definitions that I selected to make an interesting point:

| 土星 | 行星名。距离太阳第六近的行星,目前已知有六十余颗卫星,有明显行星环。属于类木行星,外观呈黄棕色,大气成分主要为氢和氦。古代称为「镇星」、「填星」、「信星」。 |

|---|---|

| 火星 | 行星名。距离太阳第四近的行星,有两颗小卫星。属于类地行星,外观呈现红棕色,大气稀薄。表面的奥林帕斯山是太阳系的最高山峰。古称「荧惑」。 |

| 金星 | 行星名。距离太阳第二近的行星,较地球略小。属于类地行星,外观呈现淡黄色,拥有浓厚大气层,温室效应剧烈,是太阳系中最热的行星。在古代,金星于日出前出现在东方称为「启明」,傍晚出现在西方则称为「长庚」 |

From these, you could make a somewhat reasonable assumption: if the word to be defined ends with the character "星", then it's plausible that the definition starts with "行星名。". On the other hand, you have no idea what objects in the real world corresponds to the characters "火星". As a consequence, you're also unable to know when this pattern will break apart: if I tell you that "流星" doesn't follow that rule, you have no clue as to why it is so—the best you can do is to learn it all by heart. What you're missing is some external information about how words or characters relate to the world.

Here's how I can prove it to you: this 星 character means "star" or "celestial body". The three examples in the table above translate to "Saturn", "Mars" and "Venus", whereas 流星 means "shooting star". Now it makes sense that definitions of planets have some bits in common that won't belong to the definition of a shooting star—in fact, this phrase: "行星名" means "name of planet". That supplementary information you were missing is what we call semantic grounding.

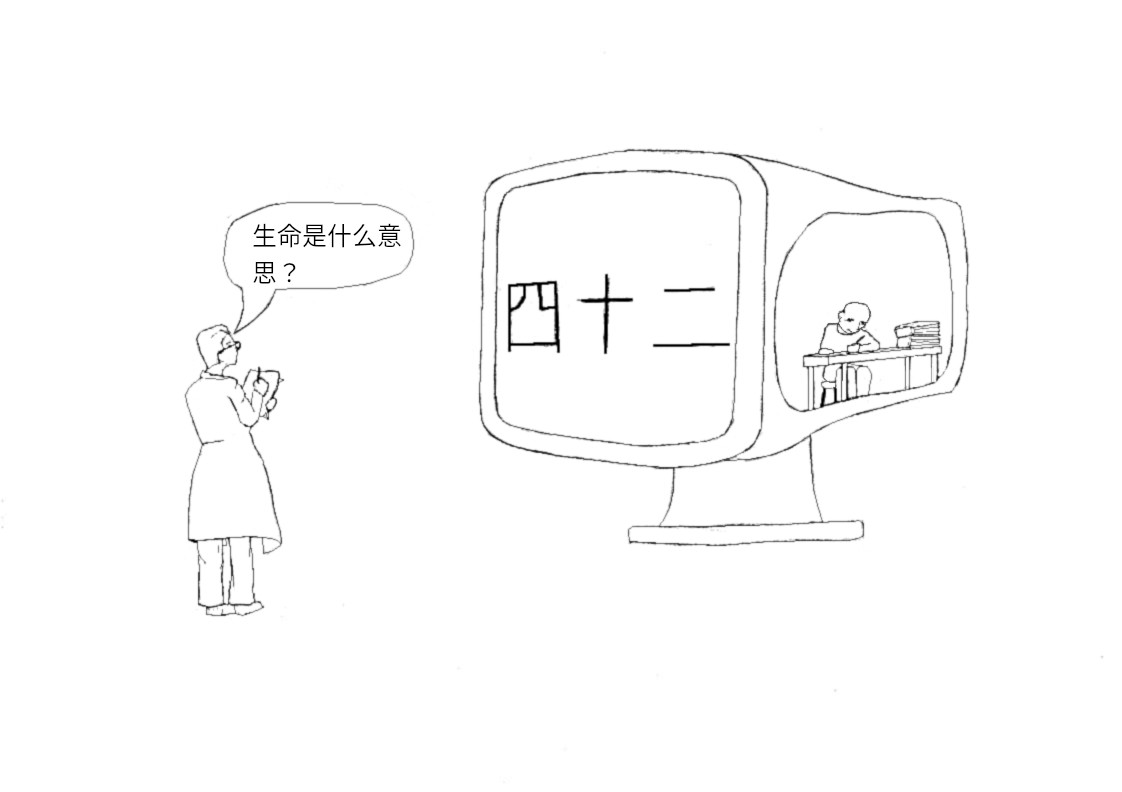

Another metaphor related to this problem is the Chinese Room Argument invented by Searle. Suppose that we have some computer software that can answer any Chinese question in flawless Chinese. Now, all computer software is ultimately just a long sequence of very basic operations, such as swapping a 0 for a 1, seeing which of two values is bigger, etc. In principle, any computatition described by a software can be done manually by a human. Here's the fun part: we take someone who doesn't speak Chinese and we lock them inside a room with the computing instructions of that software. Now if we then slip in a question in Chinese, our prisoner inside the room will be able to do all the computation by hand, and produce some sort of coherent answer. In fact, they would arrive at the very answer that our initial computer software would produce.

But our prisoner doesn't speak Chinese—that's why we nabbed them in the first place. So where does the Chinese fluency comes from? Is it the entire room itself, complete with the prisoner and the instructions, that speaks Chinese?

What's interesting with Searle's Chinese Room Argument is that it's pretty obviously targetting machine learning models. Harnad was interested in showing that text alone is not enough, and that you need some real-world interaction. Searle's positionon the other hand is that no machine can nor will ever talk consciously. A machine learning model is just a series of operations applied one after the other—how could it have a mind of its own?

Now, since I still haven't had my fill of weird brainteasers, let me present you a third one to flip the perspective a bit. This one is from Jackson, by the way. This time, we don't kidnap a rando off the street: we kidnap baby Mary. Mary is for now very young; but she's bound to become a brilliant scientist. We're not complete monsters, so we promise to free her when she's learned everything there is to learn about human vision. We even give her access to a computer, with internet and all the e-books she might wish for. She can email us the experiments she wants to be done, and we email her back the results. But here's the twist: the room where we'll lock her in is in black and white. Her computer screen only displays hues of grey.

Here is Jackson's question: would Mary discover something about color by leaving her room? Jackson's position is that there is something that's not purely quantitative about color—Jackson calls these qualitative characteristics "qualia". Colors have to be perceived, and Mary would therefore learn something by seeing red for the first time. This obviously also applies to machine learning models: if there are such things as qualia, then no matter what quantitative data we feed to our models, that won't be enough.

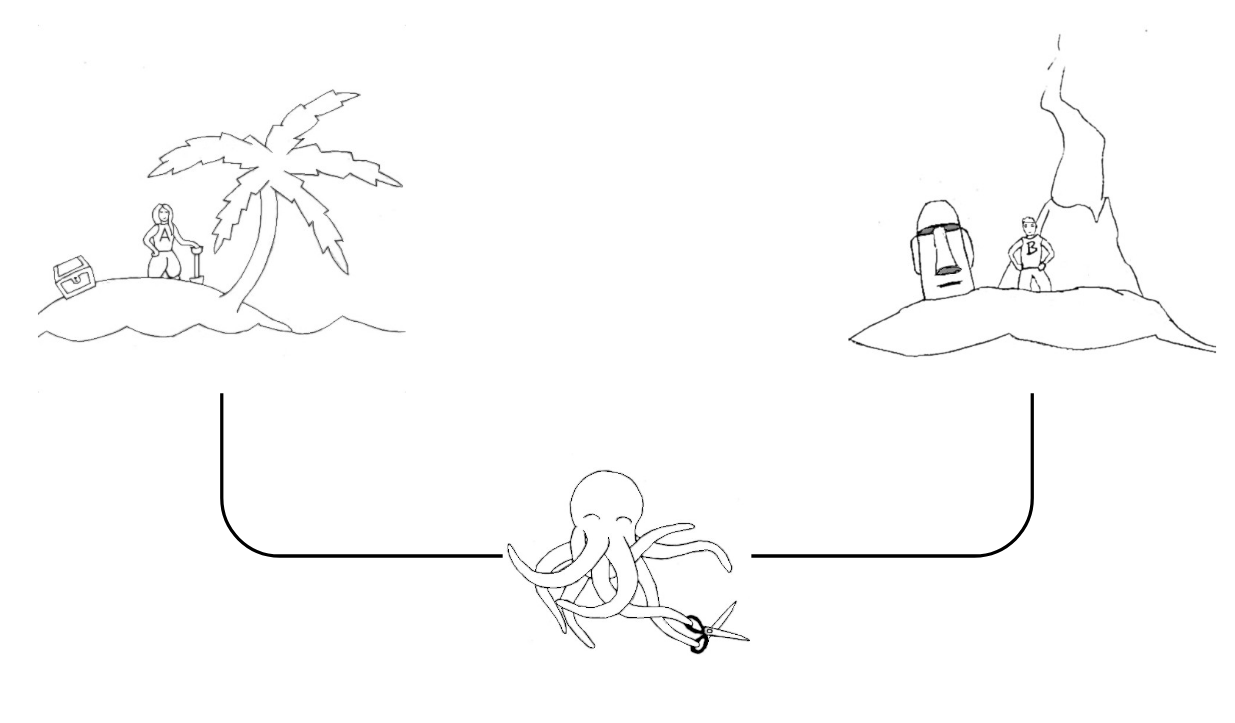

Now, here's a fourth thought experiment on the topic (this time, much more recent), from Bender & Koller. We have Alice and Bob, two English speakers stranded on two islands. They have a telegraph wire running between their islands. To combat their loneliness, they wire each other every day to talk about what they did, and exchange survival tips. But they're not the only lonely people: meet the Super-Intelligent Octopus. It leaves deep under the see—so deep it never saw the light of the day. It has no knowledge of what's life like on these islands. But it is smart. Very smart. It's tapped in the wire, and listens in on Alice and Bob's daily exchanges. Can it ever learn to speak English? Would it be able to impersonate Bob well enough to fool Alice?

Bender & Koller suggest that it's impossible for the Octopus to successfully pose as Bob. It is certainly smart, and it only has to produce morse code. It will be able to imitate the daily greetings, or Bob's verbal ticks. But if Alice suddenly veers off into a new topic that hasn't been discussed before—say she plans to build a coconut catapult—then the Octopus won't be able to come up with any decent response, because it has no reliable analogue responses from Bob that it can imitate.

Obviously, in this last thought experiment, the machine learning model is personified by the Octopus. The really interesting bit of this last thought experiment is that it does away with the question of whether the model is conscious or not. Even if the model has a conscious mind of its own—which was one of Searle's core tenets—we may have qualms about whether what it says has anything to do with the real world. In short, Bender & Koller argue that imitation is not enough to produce meaningful speech. Some sort of semantic grounding—some way of relating words to objects, so to speak—is necessary.

Why are these thinking pumps interesting to my research? Interestingly, they apply to both dictionaries and word vectors—more generally they apply to any text-based model or semantic representations. It's also likely that you can formulate testable propositions out of these. If I'm interested in seeing whether vectors and dictionaries encode the same notion of meaning, then I'm also interested in seeing whether they struggle with the same issues. I'll talk a bit more about how specifically I'm looking into these questions in future posts.